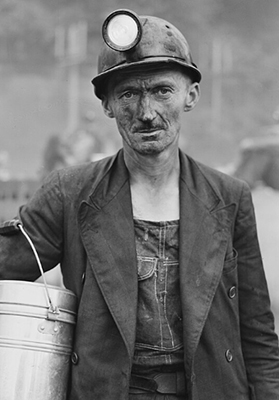

When I was a kid, there was a pop song whose words mystified me. My dad explained that it was about an American coal miner trapped in debt slavery to the mining company he worked for. The company owned the grocery store where he bought food, and his wages were set so low that he could never earn enough to escape his debt.

When I was a kid, there was a pop song whose words mystified me. My dad explained that it was about an American coal miner trapped in debt slavery to the mining company he worked for. The company owned the grocery store where he bought food, and his wages were set so low that he could never earn enough to escape his debt.

The refrain went like this:

You load sixteen tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt.

Saint Peter, don’t you call me, ’cause I can’t go—

I owe my soul to the company store.

My dad’s explanation was a real eye-opener for an eight-year-old. It was an inflection point in my growing awareness of basic economics and the harsh realities of this world. The singer laments that Saint Peter shouldn’t call him home to heaven because he still owes not only his bill but, in a sense, his very soul to the company store.

Bonded labor in that form no longer exists here in the United States, as far as I know. But severe poverty, often driven by heartless mercantilism, has been a reality for people throughout history. John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, written in 1939, was a blistering critique of the conditions farm workers faced in California at the time—working for 25 cents a day, barely staying ahead of starvation.

Bonded labor in that form no longer exists here in the United States, as far as I know. But severe poverty, often driven by heartless mercantilism, has been a reality for people throughout history. John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, written in 1939, was a blistering critique of the conditions farm workers faced in California at the time—working for 25 cents a day, barely staying ahead of starvation.

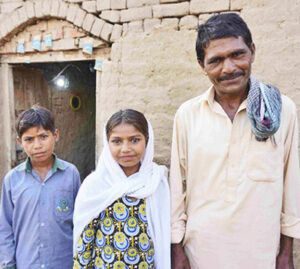

In recent months, I’ve learned about a man in his late forties who has essentially been enslaved for the last 27 years. He works in a brick-making company, often putting in 14-hour days. He earns just $3 a day, in a country where that amount buys very little.

Like the song above, he owes his soul to the company store. Legally bound to his employer until his debt is paid—a debt he can never repay at such wages—he lives in a hopeless cycle. He has a wife and three children, is illiterate, and his health is failing. He is also a Christian living in a non-Christian country.

And here I sit—my air conditioner is humming, my stomach is full from a nice lunch, and I just finished my afternoon coffee. Yet my heart is troubled, because the gulf between my comparative wealth and this man’s crushing poverty feels like an unspeakable unfairness. We often say, “We live in a fallen world,” and sometimes we catch a glimpse of the depravity and injustice that are all too common.

So, what can I do? What do I plan to do? First, I can write this and share it with you, my friends. I can ask for your prayers—not only for me, but especially for this exploited man and his young family. You don’t need to know his name or his country to lift him in prayer.

So, what can I do? What do I plan to do? First, I can write this and share it with you, my friends. I can ask for your prayers—not only for me, but especially for this exploited man and his young family. You don’t need to know his name or his country to lift him in prayer.

And for me personally: please pray as I research and take steps toward finding ways and organizations that can help this man pay off his debt and free him from the hopeless bondage he has endured for so long. It can be done. There are ways. True, it won’t change life for the hundreds of thousands of similar Christian families trapped in the same system of “bonded labor”.

But I can still help this man and his family. I’m sure not rich but I do have enough to try at least to buy this man out of utter literal slavery and into some form of labor that will lift them up to a more endurable daily existence.

But I can still help this man and his family. I’m sure not rich but I do have enough to try at least to buy this man out of utter literal slavery and into some form of labor that will lift them up to a more endurable daily existence.

The Bible says, “Do not withhold good from those to whom it is due, when it is in the power of your hand to do so. Do not say to your neighbor, ‘Go, and come back, and tomorrow I will give it,’ when you have it with you” (Proverbs 3:27–28). And of course, there are countless more verses that carry this same truth.

I personally believe in both a social gospel and a personal gospel. Jesus “went about everywhere doing good” (Acts 10:38). At times, I feel overwhelmed and crushed by the injustice and falsehood that seem increasingly pervasive. Yet the Lord continues to show me things I can do personally—things that matter and make a difference.

Maybe I can’t right all the wrongs that glare at us daily.. But I can still do what I can. As the Lord said of one woman: “She has done what she could” (Mark 14:8).

But I’m convinced there’s often more going on than what we see. King David wrote to God, “

But I’m convinced there’s often more going on than what we see. King David wrote to God, “ I believe He can do the same with people. Scripture is full of stories of those who were spiritually—and sometimes even physically—dead, yet returned to life through God’s mercy. The prodigal son was, for all intents and purposes, dead to the life he once had. But when “

I believe He can do the same with people. Scripture is full of stories of those who were spiritually—and sometimes even physically—dead, yet returned to life through God’s mercy. The prodigal son was, for all intents and purposes, dead to the life he once had. But when “

They strongly call us to something higher than the present putrid stench of politics that too often drags us down to the worst in humanity, no matter our race, nationality, or status.

They strongly call us to something higher than the present putrid stench of politics that too often drags us down to the worst in humanity, no matter our race, nationality, or status. nstead, He continues to guide and prod us along towards worthy actions that we can take to be like the woman Jesus referred to, “

nstead, He continues to guide and prod us along towards worthy actions that we can take to be like the woman Jesus referred to, “

But the real kicker came later this morning, after my daily devotion time, when I went out for a little prayer. A verse came to mind, “

But the real kicker came later this morning, after my daily devotion time, when I went out for a little prayer. A verse came to mind, “ And then there was more. When I went back inside to add that verse to my memory system, my eyes landed directly on Psalm 4:4—already written on one of my memory cards. I had evidently memorized it some time ago. But today, the Lord led me to look directly on it as I was going through my memory system, bringing it back a second time in such a personal, unmistakable way.

And then there was more. When I went back inside to add that verse to my memory system, my eyes landed directly on Psalm 4:4—already written on one of my memory cards. I had evidently memorized it some time ago. But today, the Lord led me to look directly on it as I was going through my memory system, bringing it back a second time in such a personal, unmistakable way.

Suddenly, there was a flurry of excitement as people pointed to the sky. A large helicopter, with no markings, began circling low over the camp. It then landed about 100 yards away and began unloading boxes. In the video, you can see dozens of Acehnese people, along with a tall Texan friend of mine, rushing toward the helicopter to investigate.

Suddenly, there was a flurry of excitement as people pointed to the sky. A large helicopter, with no markings, began circling low over the camp. It then landed about 100 yards away and began unloading boxes. In the video, you can see dozens of Acehnese people, along with a tall Texan friend of mine, rushing toward the helicopter to investigate. I assume the US forces wanted to avoid being identified or misunderstood in their motives. However, the aid boxes were clearly marked with “USAID,” making it evident that the US military and government were working to alleviate the suffering of the people.

I assume the US forces wanted to avoid being identified or misunderstood in their motives. However, the aid boxes were clearly marked with “USAID,” making it evident that the US military and government were working to alleviate the suffering of the people. This morning, as I thought about the current controversy surrounding USAID in the United States, those memories came flooding back. There’s a massive shake-up underway in Washington. And while I believe much of it is necessary, I also find it personally relevant, given my own experiences abroad as a Christian aid worker, often in refugee camps and orphanages.

This morning, as I thought about the current controversy surrounding USAID in the United States, those memories came flooding back. There’s a massive shake-up underway in Washington. And while I believe much of it is necessary, I also find it personally relevant, given my own experiences abroad as a Christian aid worker, often in refugee camps and orphanages.

since

since  But eclipses don’t last forever. Mine didn’t. Perhaps a secret for me was that I knew God and His son Jesus. And They are able to deliver us from the lowest hell. It was that faith, that God was bigger than my circumstances, that gave me the grace to just hold on and keep praying through a time like I’d never gone through before.

But eclipses don’t last forever. Mine didn’t. Perhaps a secret for me was that I knew God and His son Jesus. And They are able to deliver us from the lowest hell. It was that faith, that God was bigger than my circumstances, that gave me the grace to just hold on and keep praying through a time like I’d never gone through before.

“So, Mark, are you religious? Do you think that religion will solve the problems of the world today?”

“So, Mark, are you religious? Do you think that religion will solve the problems of the world today?” I can see how that question asked by someone else, seeking to understand me better and what I stand for, might have said the same thing. In that case, it would be easy to hear the sincerity in their voice and in that situation I would have answered completely differently.

I can see how that question asked by someone else, seeking to understand me better and what I stand for, might have said the same thing. In that case, it would be easy to hear the sincerity in their voice and in that situation I would have answered completely differently.

Without salvation in the afterlife, I was like a person without diving equipment, 150 meters (yards) below sea level. There was no oxygen. It was a strange, foreign world. There were beings there that were in their realm while I was not in mine. I was in extreme panic and in great confusion.

Without salvation in the afterlife, I was like a person without diving equipment, 150 meters (yards) below sea level. There was no oxygen. It was a strange, foreign world. There were beings there that were in their realm while I was not in mine. I was in extreme panic and in great confusion.

And truth was actually what I’d been looking for all along. So God gave me this experience, outside any contact with others, not a pastor, not my grandparents, not a church, but just me alone. And it worked.

And truth was actually what I’d been looking for all along. So God gave me this experience, outside any contact with others, not a pastor, not my grandparents, not a church, but just me alone. And it worked. Similarly, Bob Dylan sang in one of his songs, “There must be some kind of way outta here, said the joker to the thief, there’s too much confusion, I can’t get no relief.” As the song says, you look for a way out but it eludes you. Meanwhile, confusion engulfs and consumes you. Snippets and dark glimpses of hell, brought into contemporary music.

Similarly, Bob Dylan sang in one of his songs, “There must be some kind of way outta here, said the joker to the thief, there’s too much confusion, I can’t get no relief.” As the song says, you look for a way out but it eludes you. Meanwhile, confusion engulfs and consumes you. Snippets and dark glimpses of hell, brought into contemporary music.

What does that mean? How in the world can you “look diligently..”? But the verse goes on to say that if you don’t “look diligently”, then that is when you “fail the grace of God” and a root of bitterness springs up. Therefore it must mean that the antidote and prevention of bitterness is to “look diligently”.

What does that mean? How in the world can you “look diligently..”? But the verse goes on to say that if you don’t “look diligently”, then that is when you “fail the grace of God” and a root of bitterness springs up. Therefore it must mean that the antidote and prevention of bitterness is to “look diligently”.

Some locals came around with a boat to rescue him but the man refused, saying “No thanks, I’m trusting the Lord!” Two more times that happened and then the floods rose and the man drowned.

Some locals came around with a boat to rescue him but the man refused, saying “No thanks, I’m trusting the Lord!” Two more times that happened and then the floods rose and the man drowned.